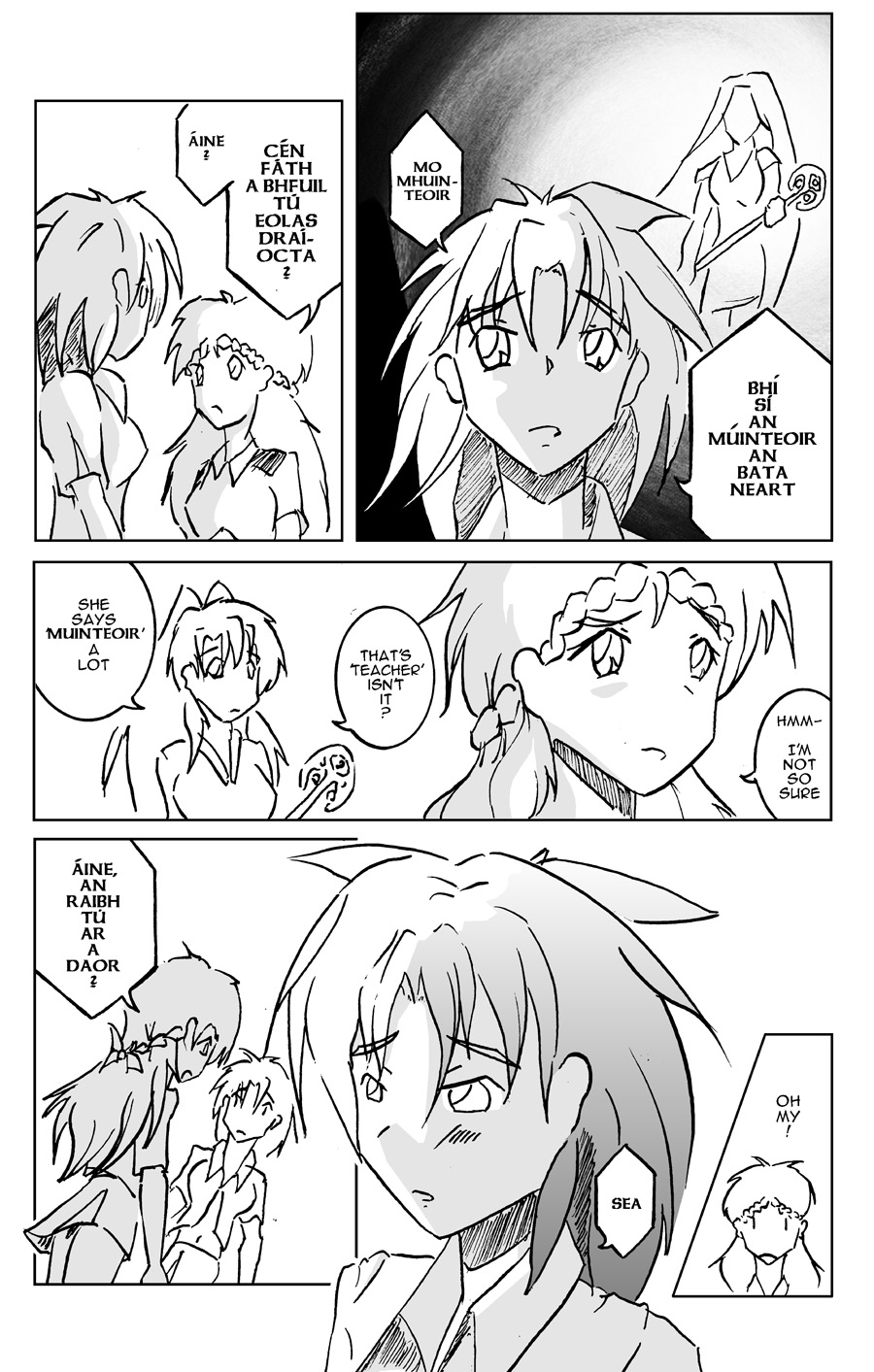

That’s a lot of Irish there, what the hell are they talking about & why has Áine’s answer shocked Fiona?

Those answers come after the break alas. Bata Neart takes a scheduled break next Friday but will return on Friday May 6th for more 🙂

Until then, a little something extra…

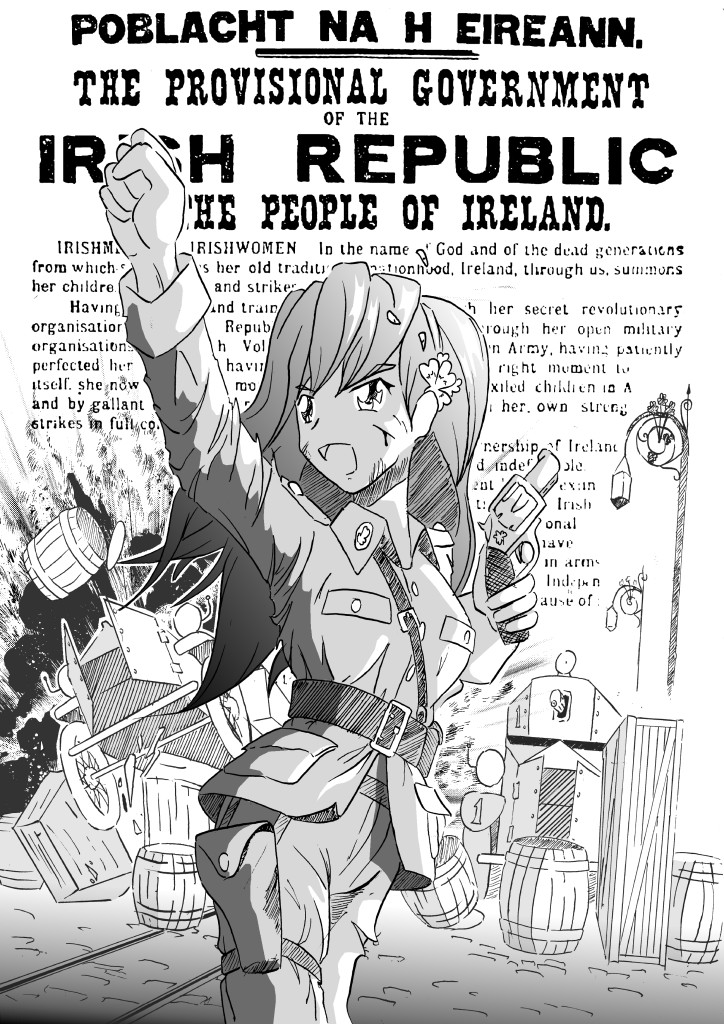

This special poster is in honor of this Sunday’s 100th anniversary of the 1916 Proclamation of the Irish Republic.

As an ex-pat I often encounter two misconceptions about Ireland that I often have to address:

- Ireland is not part of the United Kingdom (anymore)

- The conflicts between Ireland and the British have never been about religion (the whole Protestant / Catholic thing)

The upcoming anniversary which I’m illustrating here, covers a point in Irish history which I feel best explains ‘why’ Ireland is the way it is.

For those of you who are not too familiar with Irish history, 1916 is considered a fairly major year which featured an event called the ‘Easter Rising’. This happened during the height of World War 1, where many of the Irish revolutionary organisations had finally come together and planned an attempt to end nearly 700 years of British rule in Ireland.

On Monday 24th of April 1916, Irish rebels were initially successful in catching the British Army in Dublin off guard, and managed to capture large sections of the city center. Once the fighters were all in place, the Proclamation of the Republic was read out from the steps of Dublin’s General Post Office (GPO) while it was also made into an iconic poster which features in the background of my image.

Despite initial success, the resulting battle ended in failure. The British Army regrouped & reenforced with new troops & weapons from Great Britain before advancing onto the city. The Irish rebels fought impossible odds, and continued to resist the British advance as best they could, but in the end they were too few, and poorly armed.

The short lived Irish Republic surrendered.

Although the Easter Rising was a failure, it triggered the start of the Anglo-Irish War, which in Ireland is known as the Irish War of Independence. That war saw the development of guerrilla warfare which eventually wore down the British to a stalemate. By 1921, there was a ceasefire which resulted in the first ever treaty between Ireland and the UK.

Ireland attained independence as a ‘Free State’ within the British Dominion, but it would have the British Crown as head of state and also give up the northern 6 counties to another entity which would be known as Northern Ireland. The treaty was divisive, and soon after independence those divisions resulted in the Irish Civil War.

Eventually in 1949. Ireland abolished the ‘Free State’ and reorganised as the Republic of Ireland. All ties to the British were severed, and the Crown was replaced by an elected Irish President.

Due to the earlier civil war and other factors, Northern Ireland chose not to join the rest of Ireland, and remained in the UK.

And so, there you have it, a really brief summation of Irish geo-politics from the first half of the 20th century. The legacy of all this lasted for many decades, and are still present. I am however pleased to say that Ireland and the UK have long since put away their animosity, and have become the best of friends among nations.

It’s a long, dark & complex history, and I could go on for even longer about it, but I am hopeful that this snippet might give you some insight.

Thanks for reading my crazy ramblings yet again! Next time we’ll be back to the more fun magic-filled history of Bata Neart 🙂

That’s just so sad. The look on Aine’s face…

😥

It took me a few minutes to get around to it… but after reading the page, then reading the commentary, then going and reading a security article elsewhere (that I’d loaded but not read yet)… I ran this page through Google Translate. Sad.

@James Arnold Kern: It might not be as bleak as it seems. From what we’ve seen in earlier pages, Aine seemed to express a certain fondness.

But, yeah, that expression…..

@Browser: Sorry I didn’t acknowledge you–you posed while I was still fighting with my stupid, post-eating computer. Don’t EVER buy a Lenovo. ><

Correct me if I’m wrong, but my impression is that religion served as more of an ethnic tribal marker than anything else. Aren’t the protestants largely the descendants of the Scots-Irish and others who emigrated from Great Britain during English rule?

I actually have ancestors from both sides of that conflict. My dad’s family is mainly English and Scots-Irish, while my Mom’s side is mainly Irish Catholic. It may sound odd now, but even when they got married in 1962, my Mom’s family was not happy about her marrying a Presbyterian.

I’m refraining from translating it because I want to see how and what Rawr chooses to reveal. 🙂 I am seeing patterns though and recognising words (since I began poking at Gaelige) but not enough to make any guess. It makes reading this comic a lot more fun though.

@Rawr: Really love the details on the poster. Also the info dump. I didn’t know much about the details around Ireland and the UK’s relationship during the last hundred years. I like reading about history.

@Kessy: Ouch! I hope it didn’t cause any big chasms within the family and that they came to accept one another as time went by. If you love your kid, you want them to be happy no matter what and as long as what they love doesn’t threaten their life, parents should support it, I think.

There was a similar dislike during my (maternal) grandparents’ time. He was Swedish and she Danish (that’s as close to arch enemies as you can get with our history, haha). There was a lot of “not happy” on both sides to say the least. As time went by it did settle down a fair bit though.

@James & Browser & Delta: I see you’ve been peaking with Google Translate, so you already have an idea of what Áine just said. But Ashling & Aoife still need to be told, and this comes next time. The next update will reveal more 🙂

@Kessy: The whole ‘religion’ angle is just one of the misconceptions I usually have to address whenever I am asked about the various conflicts in Ireland. As you said, it was mostly a tribal marker which had little to do with religion itself. Many Protestants were Scots-Irish (descendant from Scottish colonists during the Ulster Plantation), however several were also native Irish. Most native Irish were Catholic, however some British Loyalists were also Catholic.

I also have family from both sides of the conflict, in particular the very war I described. On the Egan side, my Great Grandfather was a Loyalist officer in the Royal Irish Constabulary. When the Irish Free State was established, he was forced to flee to the UK. My Grandfather returned to Ireland a few decades and had married my English Grandmother (Making me 1/8 English). On my mothers side I have a Great Uncle who was actually in Micheal Collins’ brigade during the war and knew him personally.

The reaction of your mother’s family sounds about right for 1960’s Ireland. Attitudes have matured a lot since then, and that kind of resistance to inter-religion marriage would be very rare now.

@Jen: Glad you are enjoying this approach 😀 I appricate your patience in waiting until the next page to find out what is happening.

Glad you also like the poster and history. I just like getting the record straight on some of these things 🙂 Many people know about Ireland, and that we’ve had bad blood with the English, but feel that it’s always important to understand ‘why’.

Wow.

Yeah so my ancestry is from sides: Scots & Irish & English & Welsh.

A “Heinz 57” like myself is torn when I view & acknowledge both sides.

But bear in mind that my lineage of all these goes back to before 1800.

That’s just me…

Jim

@Jen: Well, actually, there were some hard feelings in my family, but the religion thing was only a part of it. There were several very strong personalities involved over a few generations. Most of this happened before I was born and most of the people involved are dead now, so it never really impacted me directly. I don’t really know all the details and to be honest I don’t really want to know.

@Rawr: I think it would be easier to list the nations that haven’t had bad blood with the English at some point in history. 😉 Although that would probably be true of a great many nations, not just the English.

@Rawr: Sorry, but I couldn’t help myself. I tried not to be too spoilery in my comment.

I appreciated the post on Irish independence. I’m Norwegian-Irish (mostly), and have always been interested in both heritages. That was a great thumbnail description of the hostilities. 🙂

Irish society, at the time the Bata Neart was used by Aine’s “Munetior”, was a steeply hierarchical one, where the divisions were so hard and fast that the word “slave” is not inappropriate for someone of a lower order under the control of someone of a higher order. Thus, the translation was less shocking to me.

The Scots-Irish thing is a shallower side note, actually, since its antecedents only go back to the time of St. Columba, when the “Scoti” were pushed so hard by the growing clan power of the Ui’ Niels that they moved first into the islands that became Dal Riada, and then what was then “Alba”, contesting with the Pictish Kingdom. Thus was Scotland born.

They did not come flooding back into Northern Ireland until the Royal Navy opened the way for them, and gave support wherever needed. In the meantime, many generations of “Scoti” descendants had spent over 6 centuries on both sides of the Scots-English border, providing soldiers and causing trouble, in alteration. Their movement to Ireland solved both “the Irish problem” and the threat the “Border Clans” represented to the British Crown.

Only when Ireland was definitively secured for the supremacy of the English Parliament after 1695 did the industriousness of the “Borderers” in Northern Ireland’s growing cloth weaving industry become a problem locally to Parliament. Thus, their industry was taxed into penury, sparking the movement of the Scots-Irish from Ireland to North America from about 1715 to about 1800. It is from that experience, and Scots-Irish memories, that we have to thank for the stipulations in the US Constitution against export taxes and against taxes that might differ from State to State.

@Rawr: OK, this is kind of a tangent, but I’ve been wondering how much of a cultural imprint the Norman conquest of Ireland has left. Is it just something you’re forced to read about in a textbook in school and promptly forget once the test is over? Or are there things and people that are identifiably Norman? Like “So-and-so is from an old Norman family,” or “That’s a Norman style house” things like that?

I ask because when I was doing genealogy research I read that some of the family names from my Mom’s side of the tree are of Norman origin (Morris and Dillon) and I’m curious how much significance I should attach to that.

@Kessy: There is plenty of physically evidence in Ireland of the Normans, with plenty of Norman castles and fortifications littering the island.

We learned about the Normans in school, and they usually cropped up in history lessons right after the Vikings. Much like the Vikings, the Normans were shown to integrate successfully in Ireland and ‘became more Irish than the Irish themselves’…which is a saying that croped up a lot in Irish schoolbooks for some reason.

Interest in the Normans usually stops there, when history books change gears to refer to the Normans as the English, and fun characters such as Cromwell appear. Needless to say, Irish school-children tend to get a very coloured opinion of our neighbors at this stage of their education.

You will however notice a Norman family name. We were taught family names beginning with ‘Fitz-‘ were Norman (For example ‘Fitzgerald’)

Most older castles tend to be referred to as Norman castles…often with little evidence, but it is usually a safe bet. Beyond old remaining segments of Dublin (which was a Viking city-state) there is nothing much left of Norman-era housing.

As for the significance of your Norman heritage, the particular time in history when those names appear in Ireland was kind of interesting. The Normans were the first successful colonists in Ireland since the Celts appeared, and with the backing of Norman England they established a stronghold around the Greater Dublin Area. This area became known as ‘The Pale’ which is still a name used in Ireland to refer to the Dublin Area. This is also were the phrase ‘Beyond the Pale’ comes from. Areas beyond the Pale (where the Celtic Irish were still in control) were considered too dangerous to venture out to.

I love learning about history. In high school, that was the only subject I actually go an A in. I was mostly a C student. U.S. History was fun and I really loved Western Civ which dealt mostly with Europe, but didn’t go into much detail. So thank you for the gorgeous poster @Rawr, and the history lessons, everyone.

Fitz (pronounced “fits”) is a prefix in patronymic surnames of Anglo-Norman origin, that is to say originating in the 11th century. The word is a Norman French noun meaning “son of”, from Latin filius (son), plus genitive case of the father’s forename.

Among some nobles, and a few kings, bastard sons were named Fitz (FitzHenry, FitzRobert, etc), instead of whatever family name their mother was born to or married into. Many of these gained political power.

But most Fitz’s were just normal middle class families named for an ancestor, sometimes a warrior, like FitzWilliam (Son of William), O’Brien (Son of Brien), Apowell / Powell (Son of Howell), MacDonald (Son of Donald), or Richardson (Son of Richard).

@Ryker: I never knew that the ‘Fitz’ prefix meant ‘son of’! Sweet, I love learning new stuff 😀 Welcome to Bata Neart by the way. I hope you enjoy reading it 🙂

Currently links for second and fourth pictures are broken.